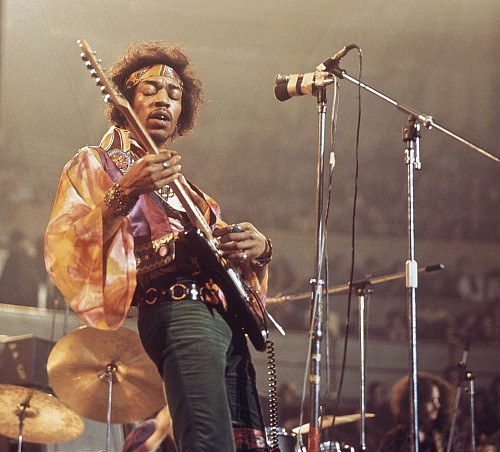

The 27 Club myth posits that the biggest rock and pop stars, and other entertainers and celebrities, are more likely to die at age 27. That grew out of the early 1970s deaths of rock legends Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, all of whom died at 27 within two years of each other.

“While the legend states that famous persons are more likely to die at 27, in actuality dying at 27 makes a person more famous than they would have been otherwise,” they state in their paper, “Path dependence, stigmergy, and memetic reification in the formation of the 27 Club myth.” “The increased attention that members of the 27 Club receive posthumously inflates our perception of the number of deaths at 27, at least among the uppermost echelons of notable persons.”

Dunivin earned doctorates in sociology and informatics from IU in August, with a focus on complex systems for the latter. He’s currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California-Davis.

Kaminski is finishing dual doctoral degrees in sociology and complex systems. He’s currently a research associate in the Department of Computational Social Science at the University of Stuttgart in Germany.

Dunivin used Wikipedia pages of notable people in creating his initial statistical model. He and Kaminksi, a friend and fellow dual-degree student, analyzed data on more than 340,000 notable deceased individuals. They found that there was no increased risk of dying at 27, but those who did received more attention.

Within five weeks of starting the work, Dunivin and Kaminski had a draft of a paper ready to submit to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The “sex appeal” of the story likely made it attractive to the journal, Dunivin said, as did the statistical modeling.

“It works in PNAS because it deals with myth making and history,” he said. “The 27 Club is a global phenomenon.”

The reality of the myth, Dunivin and Kaminski said in the paper, can be understood through three interrelated concepts: path dependence, stigmergy and memetic reification.

Stigmergy is the traces of an event or action left in an environment that can indirectly coordinate future events and actions. In this case, Wikipedia and other Web pages about the 27 Club increase visibility and create a feedback loop, they wrote.

Memetic reification describes how shared beliefs can shape reality. In this case, the myth of the 27 Club elevates the legacies of those who died at 27.

Dunivin said the goal of the project wasn’t to kill the myth of the 27 Club, because people enjoy the stories of myths, but to better understand it.

“From an analytical perspective, it’s important to take the myth seriously and look at it, even if it’s not a true glimpse of how the world works,” Kaminski said. “You learn something about how society works.”