Alumnus’ memoir describes Black student experience at IU in early 1960s

By Kirk Johannesen

February 07, 2023

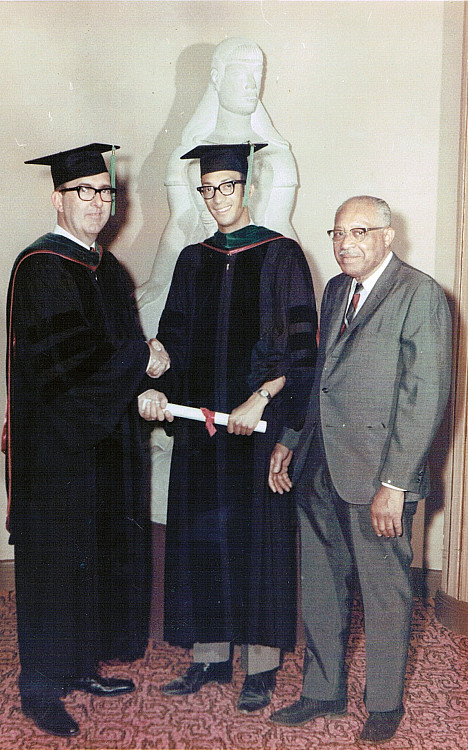

Those private thoughts are now the basis for his book, “Lucky Medicine: A Memoir of Success Beyond Segregation,” published by Indiana University Press.

Thompson, who earned a medical degree from IU’s Indianapolis campus and enjoyed a long career as a urologist, said he started writing the memoir about six years ago, but the energy of the Black Lives Matter movement and the social justice uprisings after George Floyd’s murder in 2020 motivated him to finish it.

He said the memoir explains how Black students at a school with a predominantly white population overcame barriers and achieved success. He hopes it inspires current students, saying their path to success may not be easier but is wider, with more opportunities.

The memoir also tells a part of IU history that Thompson said hasn’t been written about much: the transition between Jim Crow segregation laws and the social turbulence of the late 1960s. It shares experiences and incidents such as:

- Thompson protesting 1964 presidential candidate and segregationist George Wallace’s speech at IU, along with other Black students, but also inviting Wallace to dinner at his fraternity, Kappa Alpha Psi, to discuss issues and differences — an offer Wallace declined.

- Feeling scared for his safety after a couple of his fraternity brothers were assaulted by local white residents, who were later convicted. “Today we would label the assault as a racially motivated hate crime. Whatever you label it, it was the first time I felt physical danger in Bloomington,” he wrote.

- Being asked by a white professor at the beginning of his in-person medical school interview whether he knew how to dance.

“History is being assaulted now by so many forces and being sanitized, and by people who say we don’t want to teach this because it makes people uncomfortable. This is what you need to know; this is what happened,” Thompson said.

Thompson grew up in Indianapolis and started kindergarten at a time when schools were segregated. And although that officially changed the next year, de facto segregation persisted in the city, he said. Even when Thompson reached high school, he said there was little interaction between Black and white students.

When Thompson started at IU Bloomington in the fall of 1961, he saw a great opportunity to realize his goal — and his father’s dream — of becoming a doctor. However, Thompson saw forms of segregation, too.

“The Indiana University campus was a tolerant oasis where the burden of racial segregation was partially lifted,” Thompson wrote. “Nevertheless, like every oasis, it had boundaries.”

Black students represented a minuscule percentage of the overall student population, and students tended to stay within their racial groups in social settings.

“It was more a reflection of the Jim Crow world to which we were accustomed. Simply, they did their thing and we did ours,” Thompson wrote.

It’s also something he laments: students missing opportunities to have meaningful discussions about race and racism with more people outside their social circles. Thompson recalled having such discussions with only a couple of Jewish friends. He hopes current students don’t miss those opportunities.

“Try to be aware of the opportunities that are available to you to interact with the greater world at large,” he said. “Don’t limit yourself to a particular group. Because of the polarization in the U.S. nowadays — racial, ethnic, political or religious — there is very little dialogue going on.”

“In similar situations, we always saw the eight-hundred-pound gorilla of race in the room, but I’m not at all sure our White counterparts did,” Thompson wrote. “Those situations often produced a subtle sense of discomfort, a feeling of being patronized rather than accepted. One might think the cumulative impact of small incidents such as this one might stimulate dialogue with our White counterparts about the racial climate on campus. But to my knowledge, it didn’t.”

Indiana University Press Director Gary Dunham said it was important to publish Thompson’s memoir.

“The book insightfully deepens and complicates the story of IU, and rightfully showcases the role of African American students in shaping what the institution is today,” Dunham said. “We at the Press are particularly excited about ‘Lucky Medicine’ because the book will spark fundamental reflections on and spirited discussions about who we were, are and will be as a university.”

Kirk Johannesen is a communications consultant in the Office of the Vice President for Communications and Marketing.